a tale of two canal streets

fashion's racialized campaign against fake bags misses the nuance of geopolitical power structures.

If you enjoy this sort of fashion journalism, a paid subscription or tip is deeply and eternally appreciated.

Back in June, I was scrolling Instagram and a video from TheRealReal popped up.

Filmed with a shaky handheld quality, the camera shows a brick-and-mortar TRR store window and zooms in to a red Hermès Birkin. The caption reads: This is not a store. It will never open, because nothing inside is for sale.

My brow furrowed with curiosity—it caught my attention.

A few clicks around TRR’s social media and the story came together. TRR opened a “fake store” on Canal Street showcasing counterfeit handbags that were caught during their authentification process. It’s a temporary pop-up slated to close in September, as part of their “Summer of Real” campaign. The store hours are listed as Closed Monday-Sunday but a QR code will direct you to their campaign page. The whole thing reads to me as…corporate attempt at performance art.

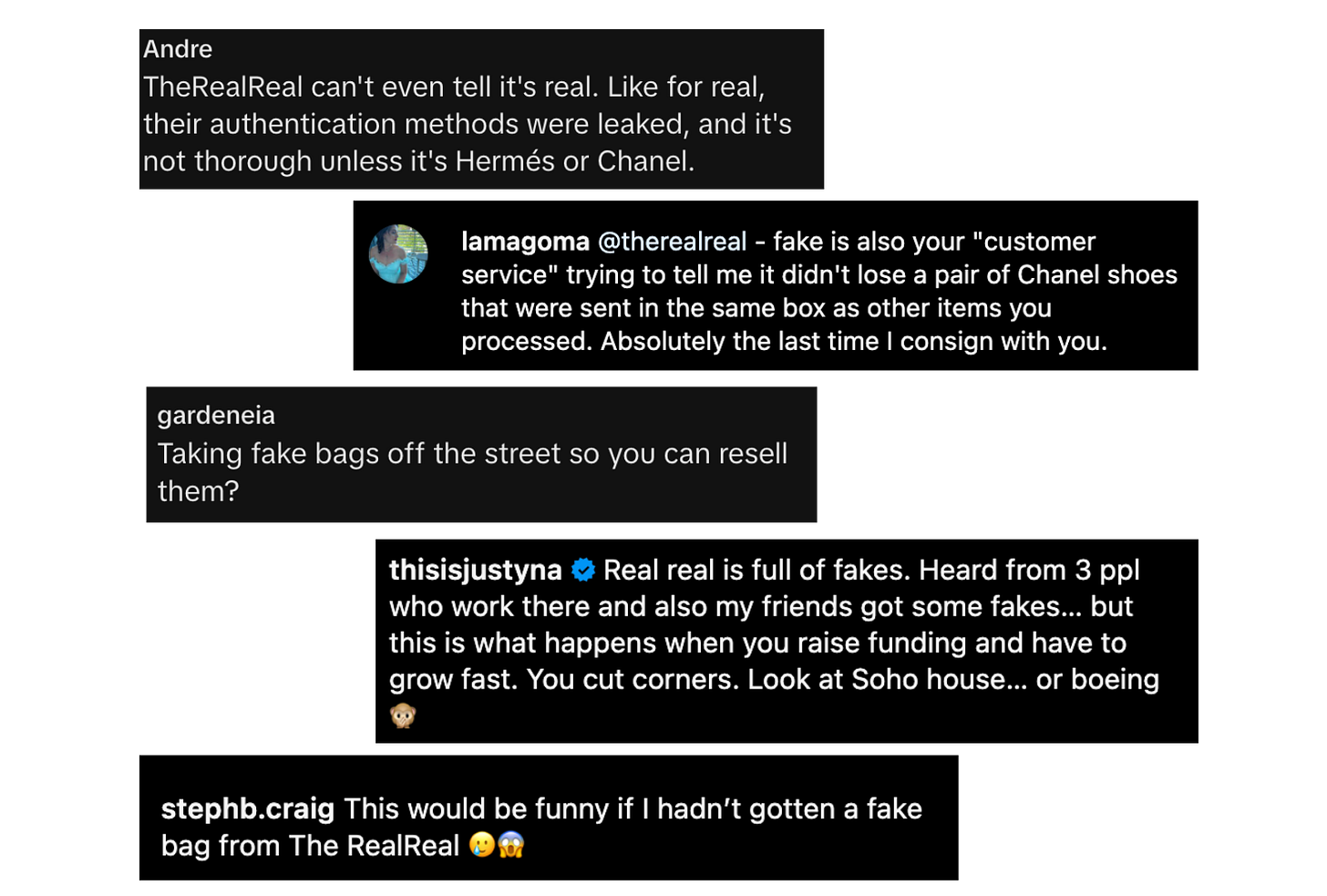

It’s a provocative, splashy concept that tries to address their notorious reputation for poor authentification. Which just scratches the surface of customer grievances like error-riddled inventory, offensively low payouts, consignor clothing mysteriously lost in transit. (Every resale regular I know has at least one nightmare story with TRR customer service).

Personally, I don’t think this pop-up was ever going to be a success in changing the prevailing public opinion around their authentification process. The social media response was largely a clap back, reflecting the low consumer trust in TRR’s authentification and general skepticism towards the direction of the company as it faces pressure to grow.

But the fake store did renew an online conversation about counterfeit bags, which is what the TRR campaign page states their goal was—“to start a conversation about what’s real and what’s fake […] not just in fashion but in every part of our lives.” If that sounds thought-daughter-y to you, I think that’s the point.

This pop-up is supposed to be cool. It’s tapping into the appetite for "chic” intellectualism, sort of like the Miu Miu book club. Over the past few weeks I’ve tuned into the event programming at the TRR pop-up. I’ve observed brendahashtag-fishing fashion types in black and white outfits. Actors and celebrities. A handful of fashion writers and creators who I personally admire for their astute commentary and critique. I have to say, seeing them attend/promote the pop-up made me momentarily forget that at the end of the day…this was a PR move by a company that wants to dominate the luxury resale market. No matter how glossy or edgy an event may seem, TRR is a publicly-traded company and their north star is increasing shareholder value.

By the way—I do not judge the writers and creators who participated in the pop-up campaign. Attending and promoting these events is often part of the job and how you keep professional relationships intact (and bills paid). And I’m sure there are other reasons that are just none of my business. Carry on.

But this is who I didn’t see in attendance at these “community events”: Canal Street vendors, neighborhood community groups, immigrant residents displaced by the high-fashion gentrification of Chinatown. If we are going to have a real conversation about the counterfeit economy, we need to include their voices.

Initially, I was just going to write about this TRR pop-up.

But a few days into my research and I quickly realized: this pop-up is merely an blip in the murky and vast scope of Western fashion’s long campaign against counterfeit goods. The story grew way bigger than I’d originally conceived, touching on everything from small acts of mutual aid between Black and Chinese vendors on Canal Street to the linguistic subversion of designer knockoffs produced in China.

The secondhand market is estimated to grow an average of 11% per year. There is big money in facilitating sales of secondhand luxury designer where authenticity matters to the consumer. What we’re seeing now—companies trying to outdo one another in having the best reputation for authenticity—is representative of a bigger power struggle. America and Europe have traditionally been the center of the global fashion industry—it’s where the power lies, how good taste is modeled for the masses to emulate. But in the past two decades, Asia’s increasing purchasing power and cultural “soft power” has been pulling global fashion’s center away from the West. By establishing this geopolitical context, we can understand these anti-counterfeit campaigns as a tactic to maintain a skewed power structure that favors the West.

Let’s. get. into. it.

knockoffs throw a wrench into the lvmh machine

Enter Canal Street: a major urban artery that runs along New York City’s Chinatown, famously known as a hub for counterfeit fashion goods. Here’s the thing though—we know the bags are not authentic designer. Vendors do not pretend to be selling an authentic Gucci bag for $70 and buyers know very well what they are purchasing.

These are not replicas trying to pass as the real thing, rather objects that are getting the original so wrong (intentionally or not) that it feels right in its own way. The originals function as status symbols and class signifiers. So when the interlocking G logo is obviously backwards, I would argue this bold presentation of artifice is actually rather…authentic.

When we talk about knockoffs, it’s usually from a Western vocabulary that relies on the moralization of intellectual property laws. We associate knockoffs with moral grayness, cheapness, poor taste. It’s a classically American belief—the conflation of wealth with good morals and poverty with ethical deviance. TRR claims "we’re not going to judge anyone for owning a shady Celine or bullsh*t Bottega.” But the usage of phrases like “shady Celine” and “bullsh*t Bottega” implies that judgement exists!

What if we interpreted the knockoff as a disruption of the geographical hierarchies of taste and class? If you’ve seen t-shirts or hats that appear to be nonsensical misspelled knockoffs of Western designer brands, you’ve come across products of China’s shanzai industry. You could call them copies, but they’re much deeper than that.

Images of these off-kilter copies trouble the binaries that grease the LVMH machine: real vs. fake, Europe as the creative genius vs. Asia as the robotic laborer.

Archivists Ming Lin and Alex Tatarsky are the creators of NYC-based Shanzai Lyric, a project that researches the cultural impact of shanzai. In an interview with 032c magazine, Lin and Tatarsky describe how the “experimental English of shanzhai t-shirts made in China and proliferating across the globe” are a study in how “the language of counterfeit uses mimicry, hybridity, and permutation to both revel in and reveal the artifice of global hierarchies.”

In their conversations with people who make and distribute shanzai garments, they observe an irreverence towards English as a meaning-making language:

The attitude is pretty much like, I don’t care. I don’t care what it says and I don’t care that it’s wrong. The shirt looks cool and I like the appearance.

Under this paradigm, FOUIS NUITTON and CÈLNÌF is neither “bad English” nor “fake French.” It’s a clever parody of power imbalance using the oppressor’s tongue. Sociologist Homi Bhabha coins this concept “colonial mimicry,” whereby mimicry by colonized peoples (intentionally or not) mock the “founding objects of the Western world.” Here, those founding objects are the Western modes of speech and print— typographic traditions and their modern digital evolutions…down to the serifed foot of a capital F in FOUIS. I also love how the mimicry of French phonetic accents in CÈLNÌF can be interpreted as a Trojan horse insertion of pinyin accents, a reference to the sinophobia in global linguistic hierarchies.

By not giving a fuck about English grammar or spelling, knockoffs can represent a rejection of what the Western world imbues with meaning and value. They expose the real fakeness our society is built upon. Lin and Tatarsky offer the example of borders as a concrete example of such a made-up construct:

Borders are the ultimate fake thing—arbitrary lines invented to criminalize and contain certain people for the benefit of others. And so the movement of counterfeits across borders is where you can really see the fakeness of the nation in action, and how dedicated the nation is to presenting itself as real through various violent activities.

a tale of two canal streets

Canal Street has been a longtime scapegoat for luxury fashion’s racialized campaign against counterfeit goods. In 2023, eBay opened Canal Street Wear, a store selling “authentic items from the most popular and coveted brands, verified by eBay Authenticity Guarantee.” Diesel might have been the blueprint for this: in 2018, they opened a “counterfeit” store on Canal Street during NYFW selling misspelled “DEISEL” products as a statement against knockoffs.

In her book Why We Can’t Have Nice Things, sociologist Minh-Ha Pham argues that Diesel’s choice of location for their store is meant to “give a nod and a wink to the racist associations of knockoff fashions with Chinese people—while entirely missing the Chinese history of the branded fake.”

The myth-making of New York as a fashion capital is partially built upon the demonization of communities like Canal Street as dangerous slums, an “urban underbelly” full of shady characters. This is how gentrification gets justified: traditional media paints a racist caricature of Canal Street, influencing public opinion to believe that upscale businesses will “improve” the area.

A good example of this is a 2018 New York Times story by Haley Phelan originally titled “Canal Street Cleans Up Nice,” later updated to “The Gentrification of Canal Street” after online responses pointed out the racist characterization of Chinatown. The gist of the article: bougie businesses are moving in and bringing $10K diamond necklaces and $48 candles with them, so now you don’t have to be scared of Canal Street anymore. The story portrays gentrification as an aesthetic glow-up of a neighborhood.

Such generalizations from establishment media erase the cultural significance of Canal Street as a community that’s existed long before you could get lattes and lobster rolls there. The Shanzai Lyric founders emphasize that Canal Street was an immigrant landing pad in New York for centuries, and that legacy has translated today into “a cacophony of languages and cultures,” primarily from East Asia and West Africa. They explain that the counterfeit economy is precisely the thing that gives Canal Street a reputation as “one of the last holdouts of authentic New York grit.”

Also, not all vendors on Canal Street sell counterfeit goods. It was hard to find primary source interviews with vendors, but here’s a great one by Liz Chow from 2016 titled “Giving Up on ‘The American Dream’?” She interviews Yu Hua, a 55-year-old Chinese immigrant street vendor on Canal Street who makes straw crafts. Here is his story:

I arrived 10 years ago and have been hawking straw craft on Canal Street ever since. On some of the things that I sell, I spent more than five hours creating them […] by hand. I realized soon that toy animals are the most popular stuff to sell, especially for the kids. I also make Chinese souvenirs to attract tourists.

Nothing has really changed on Canal Street. Except the numbers of the year. I realize my youthful enthusiasm is gone. Occasionally I meet my old customers on the street. They stop to chat or to exchange the latest gossip. But always, they have to move along quickly, always in a hurry. As I see them walk away, I can see the passage of time.

Honestly, in the United States, there is no American dream.

What makes Hua less of a craftsperson than anyone else who creates objects painstakingly by hand? The generalization of Canal Street vendors as all gray market shady characters trying to make a quick buck erases people like Hua who use the craft skills they have to make a living. Unfortunately, they also have to cater to the Orientalist gaze of tourists who want something that reads “Chinatown souvenir” like red lanterns or something with chop suey font.

For more insight into the relationships among Canal Street vendors, anthropologist Maya Singhal provides an on-the-ground account of how the counterfeit economy gives rise to acts of mutual aid among African and Chinese communities. In her 2024 article “Broken Windows”, she recalls walking down Canal Street and observing how Chinese and African sellers conduct their work amidst the threat of police crackdowns.

African and Chinese men help each other carry bushels of merchandise into their minivans. They set up tarps and tables next to each other down Broadway and watch one another’s merchandise when they have to step away. One of the sunglasses stalls on Canal seems to be co-owned by Black and Chinese men.

These are not grand acts of solidarity but minor acts of mutual aid—mutual aid ‘in a minor key’, perhaps. By helping one another to break the law as part of their hustles, and even by working side-by-side, these sellers offer a modest vision of Black and Chinese collaborations in the face of state violence and a dearth of legal means of earning an income.

I was fascinated by this case study of racial collaboration within the counterfeit economy. It comes to show that not only is Canal Street more than just bootleg bags, it’s also a living example of social arrangements and behaviors that we can learn from.

when only white criminality is chic…

In my research, I noticed a trend of journalists using militaristic and forensic terminology to describe why counterfeit activity is bad. Take the Diesel story headline by Tim Nudd for Muse by Clios: “How Diesel Disarmed the Enemy With Its Own Brilliant Knockoff Store.” Disarm the Enemy? This language equates counterfeit vending with someone pointing a gun in your face. Nudd also describes the logistics of campaign production as “a military operation.”

I’m now thinking of guns and armies. And I think that’s highly intentional, because anti-counterfeit messaging is extremely racialized. The concept of China as a foreign enemy (and its people so unassimilable) is deeply buried in the American psyche. Militaristic language is used to compare Canal Street as a site of foreign enemies—untrustworthy, exotic, lacking in national allegiance. It harkens back to propaganda that justified U.S. imperialism in the Asia Pacific.

On TRR’s campaign website, they argue that counterfeit bags are dangerous because some are traced back to “cartels and crime syndicates that fund illegal firearms, narcotics and terrorism.” The reference to cartels tap into the belief that Latin America is an inherently dangerous place (no mention of CIA complicity/U.S. imperial agenda). By this logic, you are a Good Citizen and Defender of the Homeland by buying a “real” LV bag off TRR.

And then there’s the implication that authentically produced designer goods do not cause harm or terrorism, which couldn’t be further from the truth. Just a few recent examples:

Italian luxury houses lowering costs by exploiting Chinese labor but still touting the coveted “Made in Italy” label which consumers are trained to value

Loro Piana exploiting Peruvian labor to sell $9,000 sweaters

Dior and Armani abusing workers and failing to meet workplace safety standards

Italian designer houses are highly glorified among Western fashion. “Made in Italy” still remains a signifier of European luxury tastes that Americans are encouraged to emulate, while “Made In China” carries the connotation of cheapness—despite there being a wide range of labor practices in both countries.

TRR’s social content also features people “turning in” fake bags “no questions asked.” The employee script goes: “we’re out here with The Real Real today taking fake bags off the street.” When I watched this video I immediately drew a comparison to the way politicians talk about gun buyback programs. The rhetoric is eerily similar. No questions asked, get weapons off the street, turn it into the police/authorities who will deal with it in a vague and unspecified way!!! But a bag is not a gun. And companies are not stewards of public safety, they’re stewards of shareholders.

The way I see it, TRR postures as a finger-wagging ethics watchdog telling you that a Canal Street CHENEL bag is funding terrorism—yet in the same breath, participates in the aestheticization of white criminality a lá how to accessorize like a mob wife. (I’ve previously written about why fashion romanticizes the mob over organized criminals of other racial/ethnic identities).

the future of fakes

The whole discourse on dupes and knockoffs is going to get increasingly complicated and difficult to parse out. It’s messy.

This essay focuses mainly on the scapegoating of Canal Street in anti-counterfeit messaging, but there’s a conversation about fakes to be had on every level of fashion. Like dupe culture among fast fashion, Amazon storefronts and TikTok Shop. And we haven’t even touched the issues of AI or NFT digital fashion…

Ultimately, I keep going back to Minh-Ha Pham’s definition of a knockoff, which is not an object but a racialized site of struggle over meaning and power. In Why We Can’t Have Nice Things, she concludes that “the contemporary anti-piracy movement in fashion is fueled by […] white feminist beliefs in the free market and IP rights as a moral concepts.”

I believe that if I wrote about an item and called it a dupe, the reception would be generally neutral to positive. Dupe is within the bounds of social acceptability, but knockoff is not. At this point, it’s most commonly used in our vernacular as an insult (ex: her bag looks like a cheap knockoff). Applying Pham’s framework, the difference is a racial one—white remix culture is celebrated and plastered on Vogue, knockoff culture is chastised and delegitimized as illegal.

Once we start treating the fake as an idea rather than a thing, we get closer to an honest conversation about the real artifice in this wild world of fashion.

if you enjoyed this essay, you’ll like these too :)

western fashion’s chromophobic impulse

thanks for reading!

xoxo viv

p.s. if you wanna help out with an upcoming newsletter…drop a comment on this note!

writers like you remind me that fashion is so much more than designers and status symbols with four digit price tags. it affects and informs every part of our lives, if only we’re curious enough to dig into it. thank you for taking the time and effort to write this!! <3

You’ve done such a great job researching and writing about this topic, thank you! Sending it to lots of people because it provokes such interesting reflection.

Part of that reflection (for me) is thinking about the idea of “dupes versus knockoffs” and how the cultural stance on “knockoffs” has changed from one of shame (remember the Samantha Fake Fendi Sex and the City episode?) to one of subversion and cleverness (“oh you stuck it to the rich French conglomerate! And saved money, you’re thrifty!”) We no longer universally consider it moral to buy the “real version” — the culture has a stronger anti-large-corporation stance. We recognize that even the large corp has sourced its ideas from somewhere (it exists in the context of everything that has come before…🙃) We are collectively aware, more than we ever have before, that even the famous design houses that are scared of IP theft often commit outright IP theft themselves from subcultures without the means to scale their visions. You can really see that cultural shift via a 2007 New Yorker article about a lawyer who “hunts down counterfeiters.” I consider it progress, however minimal it may be, that it felt jarring to see a New Yorker article talk about Chinese people that way. The article [1] only dared to pose this question as an aside: “[Some people] suggested that he was doing something bad, putting helpless immigrants and desperate Chinese laborers out of work for the sake of making a bunch of rich French people richer. Harley could tell himself that he was protecting the real against the fake, but then he thought back to when he was a kid, before brands got so important—when, as he remembered it, people used basic, generic goods, when a sneaker was just a sneaker. Compared to that basic thingness, brands themselves seemed fake.”

To some extent, it’s also worth noting that the Canal St sellers aren’t actually cannibalizing the big design house’s customers and that they need each other. They’re in a strange symbiosis. The Canal St sellers need the luxury houses for product marketing (making a certain style or brand popular with consumers.) The big luxury houses actually view the Canal St sellers as a means to measure their cultural caché. No wonder they’re opening stores on Canal St. It was kinda surprising for me to read this from the Diesel founder: “Rosso himself has never purchased anything on Canal Street, but he often visits to see which are the most copied. “If someone copies you it means that your brand is worthy and top of mind with consumers,” he said. “It’s a sort of real-life market research.””

But while I agree that the “real” goods are also flawed, I disagree that they’re morally equivalent on two fronts. The first is in regard to labor: yes, both might have terrible labor conditions, but a very “legible” and concentrated target in the form of a large luxury house is a much better foe for a government or even an activist consumer base that a more “illegible” and grassroots network in the Pacific Rim. I don’t think that all of these operations are sweet small businesses — maybe some are, but the factories and the production behind some of these sellers is immense. I think it is very likely that without making claims on the current state of labor practices, it’s easier to protest/regulate the Big Corp to fix the issues.

The second is in regard to climate: I think the big fashion houses are better targets for regulators here too. The recent EU regulation CSRD is certainly going to push much more rigorous standards on them in a way that isn’t possible for some of these other operations that are operating more “off the grid.” I get why this is the case, and more power to them, but from a climate perspective, the big fashion houses have to consider materials innovation or supply chain innovation to make this all work. They’ve also been leaning into “sustainability” as a luxury concept (this might actually be true, given that climate change will mainly impact the global south…) which is in equal parts laudable at the individual entity level and problematic societally. It’s probably accurate to say that you will be “carbon neutral” if not negative (in a genuine, science-backable sense) with many luxury purchases in a way you will not with the other goods that may be produced and sold as “dupes” or knockoffs.

Ultimately, I’d say the issue that complicates both of these things for me — something both Canal Sts share — is related to over-consumption and logo obsession. Hard to think about that too.

Thanks again — really thought provoking!

1. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/03/19/bag-man